AUTHORS

Hannah Kent Q&A

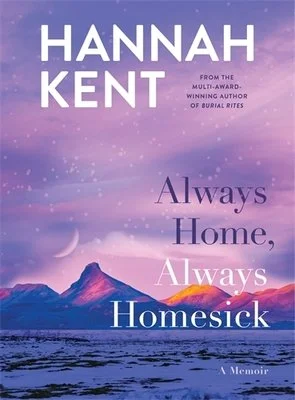

Hannah Kent is an award-winning author and screenwriter. She is the author of the bestselling novels Burial Rites, The Good People and Devotion, and her original feature film, Run Rabbit Run, premiered at the 2023 Sundance Film Festival. Hannah is the co-founder of Kill Your Darlings and her writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Guardian, The Sydney Morning Herald and Vogue Australia among others. Her most recent book is Always Home, Always Homesick.

Why do you tell stories?

It is not so much a choice as a compulsion. Ever since I was a very young child I have sought understanding, comfort, knowledge and reprieve in stories: both in reading them and telling them. Storytelling is my means of divination; a way to make sense of things, to ask questions of the world and myself, to commune with something that extends beyond the boundaries of my own lived experience. It’s also a lot of fun.

Describe Always Home, Always Homesick in one (or two) sentence(s).

Always Home, Always Homesick is my love letter to Iceland, and my reckoning with what it means to forever be held between places and people, the living and the dead, the past and the present.

You have now written three (sublimely brilliant) works of fiction and this is your first non-fiction piece. Did you have to apply a different sensibility to the composition of this book than you have used previously? Is there more bloodletting in memoir?

There is bloodletting in all writing, I think. I mean that both in the sense of catharsis and sacrifice.

I did assume memoir would be more straightforward to write, mostly because my fiction requires so much research. I was wrong, of course. Annie Dillard once said, ‘You have to take pains in a memoir not to hang on the reader’s arms, like a drunk, and say, “And then I did this and it was so interesting.”’ That became the challenge: not finding what to put in, but choosing what to leave out. Tricky, because every memory feels significant. I ended up cutting over 30,000 words at quite a late stage of the drafting process.

What is a kvöldvaka?

A kvöldvaka is an Icelandic word that does not easily translate into English. A literal approximation might be ‘evening wake’ or ‘night waking’, but the term refers specifically to the historical Icelandic practice of gathering in the main room of a turf house (where everyone slept together) once the day’s outside labour was done, to listen to stories before bed. A literary congregation to withstand the darkness outside.

What are Icelandic ghosts like?

There are many types of Icelandic ghosts. Draugar are restless spirits able to leave a place of burial and wander about, and are probably most like the ghosts of contemporary Anglo understanding: they often have unfinished business or seek revenge, although they interact with the world in a more physical way. They can get worn out and age in the same ways as the living, and there are many stories of people fighting draugar or being killed by them. Those with magical ability can also summon draugar from the dead, and these zombie-like ghosts are referred to as uppvakningar (‘the woken up’). An útburður is the spirit of an unwanted infant who was taken outside to die of exposure. They are often heard wailing and crying, wear the rags they were left in, and can cause the living to go insane. A skotta is a female ghost, a móri a male spirit, often violent. Fylgjur are ghosts attached to certain people, and may appear as shadows or animals. There are many instances of ghosts haunting people for the entirety of their lives, and sometimes they continue their haunting of families across generations.

Tell us about the significance of dreams in the writing of both this book and Burial Rites?

The beauty of hindsight is that it allows a far-reaching perspective in which patterns and repetitions are discernable. Going through ten years of notebooks and correspondence, I was stunned to see how frequently I wrote about dreams, and how they not only led me to the writing of Burial Rites, but shaped that writing. I always knew that many of the people upon whom Burial Rites is based had significant, even fateful dreams during their lives, but it wasn’t until I had the perspective of twenty plus years that I was able to recognise the overarching significance of dreams on all sides.

What were you under the influence of (books, authors, ideas, art, or anything else) while writing this book?

Music, mostly. I often listen to music while I write, and in returning to Burial Rites, I returned to the artists who accompanied that novel and their atmospheric influence: Laura Marling, Sigur Rós, Basia Bulat, Florence + The Machine, Steindór Andersen.

This is a question you asked yourself in preparation for your keynote at The Reykjavík International Literary Festival 2023: Is an Icelandic novel still an Icelandic novel if it isn’t written in Icelandic?

My intuition is to say yes, of course – Iceland is now home to many writers who write in languages other than Icelandic. But I am willing to hear all sides of the argument. I’m actually more interested in the discussion than in finding a definitive answer.

Which adjectives by readers and reviewers used to describe your writing, most please you?

I’ve never been asked this before! Moving, probably. Beautiful.

Tell us about your natural writing habitat.

I write at home, in a study with two desks (one for my desktop computer, the other for notebooks and research sprawl), and big bookshelves. It has a door I can close to better step inside my mind, and a window to remind me of the world outside it.