AUTHORS

Catherine Lacey Q&A

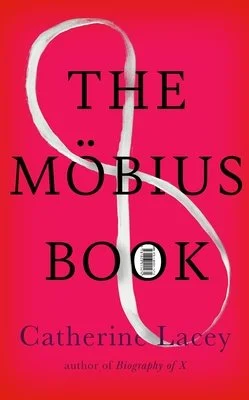

Catherine Lacey is the author of the novels THE ANSWERS, NOBODY IS EVER MISSING, PEW and BIOGRAPHY OF X, and the collection of stories CERTAIN AMERICAN STATES. She has won a Whiting Award, was twice shortlisted for the Dylan Thomas Prize and was named one of Granta's Best Young American Novelists. Her books have been translated into French, Italian, Spanish, Dutch & German. She was born in Mississippi and is based in New York and Mexico.

Why do you tell stories?

My beloved high school English teacher, Mr. Watkins, recently asked me this and I think this is the best answer I can give right now so I’ll repeat it: Writing provides the illusion that you can keep your thoughts or memories or ideas forever, even though all your thoughts and memories and ideas are always half-vanished before they ever exist, that is, if they ever even existed in the first place.

2. Without talking about plot in any way, what would you say your book(s) are about?

It seems I have never for one day of my life been able to take existence itself for granted. Everything absolutely baffles me and nothing makes any sense and I am unable to write a book or story that doesn’t have at least some of the confusion in it.

3. In the blue side of the Möbius strip (memoir-side), the narrator questions the increasing failure of fiction to provide the treatment or balm she once craved as both a reader and a writer. Has this been your experience also?

I know it’s polite to talk about the “character” narrating a memoir, to draw a distinction between the “character” and the author herself, but I feel pretty comfortable saying that that the voice in the memoir is as close to the self who wrote it as I could get. So, yes, at the time that I was writing that part of the book— pretty much all of 2022— I couldn’t read much fiction and I didn’t write any fiction. I have, thank god, recovered from this affliction. I think an inability to step into a fictional world is an unfortunate side effect of grief. Not all, I hope, are so unlucky.

4. Perhaps a related question, there is a tendency for readers to blur the distinction between author and narrator in fiction, but especially in poems and autobiography. What did you want to interrogate for yourself about this distinction? Is publishing both memoir and fiction within the same book a tacit acknowledgement that this blurring will happen whether the author wishes it to or not?

There are times in everyone's life—times of illness or grief or catastrophe or betrayal or simply change— that make life itself entirely too vivid. Everyone goes through these moments at one point or another and one way of looking at those times is that your sense of yourself has been challenged, or the divide between the self and the other blurs, or that the distinction between yourself as a “self” and yourself as a “character” in your life has broken down.

I wrote the nonfiction side of this book as a kind of life raft in such a moment; during the year that I was writing it, I wasn’t really able to do much else. But then life changes and you see the story you’ve just lived quite differently than what it felt like when you were in the middle of it. That’s interesting to me and I wanted to make a book that was both inside a personal crisis, livid, confused, hurt, but also outside of it. The book was an answer I made for a period of years in my life, as all my books are. This time, however, the part of my life that was necessitating the book was more exposed than it usually is. I wouldn’t say I made the choice to blur this line. I would say I had some bad/good times that sort of blurred me. In the end I recommend it. I recommend getting blurry.

5. After growing up in a religious home, how has the narrator’s underpinning or understanding of faith shifted across the writing and adult romantic life?

I’m still very much in the middle of this shift! After being a bit of a Christian evangelical fundamentalist— more through my own impulses and some extreme summer camps than from any pressure from my family— I swung in the other direction for a while. Certain experiences have led me to believe I was likely wrong in both extremes. I don’t think the nature of existence is something anyone can get total clarity on, or come to a place of finality with, so I plan on being here in the middle of this confusion for a good long while.

6. There are frankly some brilliant smashing scenes. The tea cup and crow bar. The pallet bricks. The car crash. Did writing this book feel like an act of bearing witness to the destruction of your own life, before the careful, painstaking work of rebuilding could begin?

Many years ago, I spent a very sad Christmas alone in New York City. I had a box of old, probably somewhat valuable china that had been given to me by someone I was no longer speaking with. I felt I had no use for the china; the china also seemed a bit cursed. I lived in a building that is presently slated to be knocked down, and I had access to the roof. I went to the roof with a stack of plates and I threw them one by one into a brick wall. Suddenly, I didn’t feel so awful anymore.

7. In the fiction version, blood pools from underneath the neighbour’s door, while two friends in the next apartment discuss the disintegration of their respective relationships. The blood—both physically and metaphorically—seems to demonstrate a sense of emergency in the women’s emotional lives, as well as represent the lovely wreck of our bodies. What does the blood represent for you?

With fiction I don’t really think about symbols as much as I think of the logic of the story, and whatever the story needs in order to function. In order for these two women to be in the apartment talking for a whole 100 pages or whatever, I knew an underlying tension needed to be present in the narrative. The blood under the door arrived immediately, without much consideration, and I never questioned it because it seemed to do what I needed it to do in the story. What it represents depends on the reader, in my opinion.

8. What were you under the influence of (books, authors, ideas, art, or anything else) while writing this book?

Oh so many things— I put a whole page of works consulted at the middle/end of the two sides, but also the influence of my friends cannot be understated. Platonic care was probably the most important ingredient in the writing of this book.

9. Which adjectives by readers and reviewers used to describe your writing, most please you?

It’s an honor for one’s books to be read at all, especially in this perilous century of AI slop and the wilful and widespread embrace of the enshittification of the human mind. With that in mind, I accept any and all adjectives— slanderous, approving, suspicious or awestruck as they may be. In order to prefer a certain reading of my work, I would have to believe that I know the most about it, or that I am the one who can understand it best, and in fact, a writer probably knows the least about her work and barely understands it at all.

10. Tell us about your natural writing habitat.

I am writing this from my kitchen counter with my dog muttering at my feet and my husband doing his own work beside me. Sometimes I work in the guest bedroom that has a desk, and sometimes I work on the couch, and sometimes in a café. I think mornings are better for fiction and afternoons work better for essays. Beyond that, I’m not too picky. I tend to adapt to the circumstances.