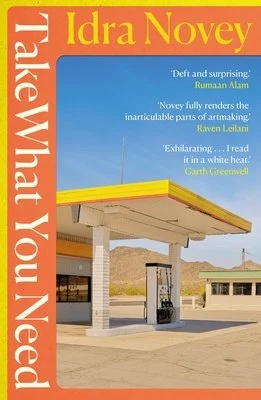

AUTHORS

Idra Novey Q&A

Idra Novey is the award-winning author of the novels Ways to Disappear and Those Who Knew. Her work has been translated into a dozen languages and she's written for the Atlantic, the New York Times, and the Los Angeles Times. She teaches at Princeton University and in the MFA Program at New York University.

Why do you tell stories?

Stories are my way of figuring out how to live with contradictions. When an instinct of my own, or an interaction with someone else, resist easy explanation and I start going over them repeatedly in my mind, I now recognize that as a moment I’ll likely revisit, in some way, in whatever work of fiction I write next.

Describe Take What You Need in one (or two) sentence(s).

I loved Kristen Martin’s description of it this week for National Public Radio: “a novel about the ineffable impulse to make art, wedged into an exploration of what happens to towns and people left behind.”

Jean’s giant and intricately layered metal sculptures bring to mind the work of Louise Bourgeois—what is Bourgeois’ influence on you as a writer? Did you have a definitive vision of what Jean’s art looked like or felt like as you wrote?

Bourgeois has indeed been an ongoing influence. I found a beat-up book of her interviews years ago at Bull Creek, the flea market where Jean goes in the novel to find materials. I had the idea early on that Jean would eventually weld a sculptural coffin for her dad, with Bourgeois's Destruction of the Father in mind. Bourgeois’ insights on sexuality and power, on her father, aligned potently with how I imagined Jean’s artistic drive, and my own. Bourgeois recognized the libidinal forces that continued to compel her, late in life, to keep experimenting and taking new risks with her art.

The novel shifts back and forth between the voice of Jean, and her estranged stepdaughter, Leah, and from slightly different points along an overlapping timeline. Can you comment on your process and choices in structuring the narrative this way (as a reader, the bifurcated narrative structure is vividly powerful)?

Thank you, and what a wondrously precise way to describe the novel, as having a bifurcated structure. Leah’s chapters occur in the present tense, to highlight her impulsive choices in reaction to the news updates on her phone and the shocking events happening hourly in the United States. I wanted her chapters to have that present-tense kind of immediacy.

Jean, however, is welding her sculptures at a remove from that kind of constant input from the larger world. Her isolation has contributed to her estrangement from Leah, but it has also allowed her to stay true to her own instincts as an artist, to “hear the call of truth when it comes,” as Rachel Cusk says, of artists who seek a remove from the ongoing judgment of others.

Jean lives in the Allegheny Mountains of Appalachia, in a desolate and hardscrabble neighbourhood of lawlessness and poverty—a resonant backdrop for writing Trump’s America onto the page as an artist. Can you comment on the setting?

Sevlick, the invented town in the novel, is an amalgam of various towns in the Allegheny Highlands where I grew up, and where parts of my family have lived for over a hundred years. I’ve known many quiet young men like Elliott, who have limited options and who work in situations where they don’t have the luxury of being able to speak their minds. Elliott’s artistic sensibility doesn’t cohere with prevailing stereotypes about young rural men, who are often portrayed in reductive, demeaning caricatures. It isn’t in his nature to be confrontational, and when he does finally speak up, he gets kicked in the face.

In my early drafts of the novel, I was ambivalent about how explicit to be about Elliott’s conversations with his friends, or about the Trump slogans on the flags in the area. The deeper I got into the novel, though, the less necessary it seemed to name the slogans. I wanted the novel, the questions in it about political polarization, to transcend our particular moment.

Jean and Leah’s relationship has many discordant notes of difference between them in terms of economic status, precarity, age, gender dynamics—what is at the heart of their relationship?

Jean found deep pleasure, and meaning, in becoming Leah’s stepmother. Leah knows Jean’s parental devotion to her was genuine and formative to the adult she’s become. Despite the impasse they reach, and the years of estrangement that follow, they continue longing for each other. I think that longing is at the heart of the novel, and of their relationship. I couldn’t find any novels about the psychic toll of polarization between urban and rural women, or at least not addressing the aspects you mention in your thoughtful question. We are in a time when there are many ways to delete a relative, to press a button and make them disappear from the contact list on our phones. How does that option change us? Leah comes to regret her decision to delete Jean from her life.

Jean and Elliot’s relationship is also asymmetrical, but they share a deep bond nonetheless. Do they both take what they need?

Yes, I think you’re right—they do both take what they need! The title connects to the biblical proverb about binging on honey: If you find honey, eat just what you need, lest you have too much and vomit it up. We are a species prone to indulgences. When we find honey, it’s hard to resist taking just what we need, even knowing the likelihood that a lack of self-control will leave us hunched over, hurling, and feeling ill. In the beginning of the novel, when Jean tells Elliott’s mother to draw as much water from the spigot as they need, they both know there will be implications to this offer. It is about far more than just water.

In what ways is artmaking both Jean’s salvation and great burden?

Art offers Jean a way to coerce her dreams into forms that can be experienced in waking life. She doesn’t have the opportunity to find many people who can understand, and appreciate, the intensity of her artistic drive. Why some people are born with a hunger to make art and experience it, and others are not, is such a mystery. I don’t have any relatives who have placed art or writing at the center of their days the way I have, and the way Jean does in the novel. I drew on my own bafflement to write the scenes in which Jean wonders why she is so driven to make art.

When and where do you write?

My ideal writing time is six am with a cup of tea. Often, I have to take my dog first, and if it’s a weekday, I have to wake up my children and get them out the door to school. During the semester, my morning writing stretch is far shorter on days I have to teach and catch an early train to Princeton. As many mornings as I can, for however many minutes are possible, I try to sit down in the early morning with my tea and assemble some sentences, on the chance those sentences may lead to something more.

What are three things that sustain you as an author, or while you’re writing?

Reading sustains me. Also listening to other people, the surprise and pleasure that can happen in a great conversation. On a more philosophical level, I think Edmond Jabes was onto something when he said it is not certainty which is creative, but the uncertainty we are pledged to in our works.

Bonus Question:

Name three books that you couldn’t live without, or that were crucial to the writing of Take What You Need.

Three that were crucial to Take What You Need:

Barbara Comyns: The Juniper Tree and Our Spoons Came From Woolworths

Louise Bourgeois: Destruction of the Father / Reconstruction of the Father: Writings and Interviews, 1923-1997

Helen Oyeyemi: Gingerbread